Contemplations of the Built World: the architecture & Philosophy of Louis kahn

So today I want to talk about the architecture of Louis Kahn. Kahn's architecture tells a larger story about a cultural shift happening in America in the first half of the 20th century. This was during a time when the culture was shifting into modernism and it was departing from the historical traditions of the past. It was ignited by these ideas floating around that can be originated in the Enlightenment. So, these ideas of rationalism, individualism, science. It was a reaction against the historical precedents of the past. So, in the modern movement, things like efficiency, profit, abstraction, and mechanization really drove this new form of architecture. So, this was the time period to set the stage when Khan was really starting to kind of get into his rhythm as an architect. And so, it was a tumultuous time. It was a time of a lot and he was having to kind of grapple with these two different schools of thought. He was developing his architectural voice. And many of his colleagues and contemporaries, they either chose to kind of dogmatically adhere to this new modern paradigm, or they chose to stay, adhere to these historical traditions of the past. And Khan believed that there was some sort of blend he could extract the essence and these principles that he enjoyed from both of these epochs and not so much synthesize or harmonize them together, but really take what he felt was the most authentic elements from each one of them and create his own architecture from that. So, really what he was able to do was create a body of work that was unique, yet it still was also relevant in this modern era because it spoke to some of these modern principles, but it was definitely unique compared to a lot of the other work happening at the time. Let's say architects such as Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, a lot of modern architects were dealing with this concept and principle of thinness. So, they were dealing with thin planes, glass facades, individual free-floating columns, that sort of thing. And Kahn's work was very different from that. It was noticeably different from that. He dealt mainly in these areas of mass and volume, so he enjoyed more mass, more heavy scales. So, you think of an architecture in the modern era with thin planes, floating planes, and then you think of Louis Kahn's work, and it was very heavy. It felt rooted into the earth, it felt rooted in historicism, still while also being modern. So, it was a very interesting thing that he was able to achieve. Kahn stripped historical buildings of their historical pastiche, and he removed the unnecessary ornamentation that you'll find in historical structures. He introduced asymmetry and he celebrated the unadorned surface that you would see in a lot of modern work. He was classically educated in the Beaux-Arts tradition so that was a school in France that celebrated these ideas of historical architecture, mainly rooted in Greek and Roman architecture. But the Beaux-Arts was really about mass, large-scale, symmetry, permanence, and monumentality. And he, like I mentioned, he enjoyed these principles very much and thought that there was something that, you know, really resonated with the human and our sense of space in that type of architecture. And it was challenging for him to completely abandon it for this new modern paradigm.

So, a defining moment that is often seen as a shift in Khan's body of work and also in his career path is a trip that he took in around 1950 to Rome, Greece and Egypt. So, on these, in this trip, he was able to visit the historical architecture of these amazing cities and it profoundly impacted him. He kept many sketchbooks where he studied the scale, the mass and the size of these buildings in his book and that's recorded. And it was something that, again, he couldn't quite let go of that in his work and he felt that something resonated with him on a very deep level and he needed to really bring that back or bring that, preserve that in his work.

So, Kahn started off in his architectural philosophy with this idea of monumentality and permanence of, most likely he would have derived that from his Beaux-Arts training with monumentality and permanence, you know, he's looking at these historical structures and they exuded these, these characteristics. They were very solid, very grounded. They had, let's say, calculated processions. They were hierarchical. So, Khan began working through his philosophy using these ideas, monumentality and permanence. Because of what was happening in the culture at around this time when he was deriving these things, you had challenging political movements happening, you had world wars happening. I think that idea of monumentality and permanence hierarchical systems may have been not accepted when Khan was talking about these things. So, I think that may have been a reason why he shifted to this concept of order. So instead of monumentality and permanence, he shifted over to describing his philosophy in terms of order.

So, what did he mean by order? Khan thought that in order to describe an architectural philosophy, he needed to trace its roots back to the human conditions and the base of the human condition. So, he started out asking larger questions about the human being. So why are we here? What's our purpose? In that questioning, he derived this idea of order. He felt or he described order in terms of a poetic metaphor that poetic metaphor was silence and light. So, silence he described as this time of conception of imagination when thoughts and feelings are still within the human being they have not been brought into the light, they're in silence. They are in our heads, they embody all the potential, but they have not been brought into the light or been brought into physical form. In terms of, so that's how he would describe the silence. When he said that silence and light, what light meant is, it always takes something to bring what is in our imagination, what has potential, it always takes something to bring that into light. So, he believed that art and architecture was you know that mechanism that was able to communicate between those two worlds so when something it was in the light it was brought into the physical world was manifested. It was created. And that in Kahn's terms kind of described this idea of order. So something always has to be having potential, then it can translate or transmit into something of light. So, he describes the idea of order using the metaphor of silence and light, and then Khan said that silence is the realm of potential where something such as a building resides before it is conceived. And light is the realm of realization and is the medium through which things transcend from potential into realization. And then he kind of followed that by saying, okay, to move between these two worlds from silence into light, there needs to be what? There needs to be a desire.

So again, this goes back to this original idea of contrasting his philosophical roots and architecture back to the human condition. So, he said that humans have desire. All humans have needs and desires. Our primitive selves desire food, water, shelter to exist. And those are innate inside of us. We share many of these desires with animals. However, Khan believed that humans were unique in that we had a conscious awareness, and we have the capacity to conceptualize the past and the future in our minds. And our ability to do so allows us to desire things in the past and the future. Our desires speak about our future potential and our desire for achievement, love, service, and protection. Khan outlined three primary desires that humans typically exhibit that are unique and beyond what the animal kingdom shows, and that's the inspiration to learn, the inspiration to meet, and the inspiration for well-being. All three of these cater to the desire to express ourselves ultimately. We aspire to develop ourselves and actualize ourselves according to our future visions and projections. So, you see how we can kind of start looking at this thing. So, kind of established silence and light. And then he said desire was the kind of mechanism to transmit between silence and light. It's our intuition. It's our, it’s inside of us to want to desire these things. The three desires that Khan laid out. So, society, in order to facilitate-- let's call it the nurturing of these different desires in our communities. We created what Khan would call institutions.

So, he felt that institutions were the organizations that helped us to structure, nurture, and again facilitate these desires and grow these desires, develop these desires inside of our culture. Every institution inside of our culture typically had a work of architecture to house that institution. So, John Lobell explains this a bit. He says that the desire to learn gives us the school, the laboratory, the library. The desire to meet together gives us the town square, the assembly hall, and the community center, and the desire for well-being gives us the place of spiritual realization. Khan believed that institutions were fundamental to human development. They were there in essence to be the kind of midwife to help develop and bring to fruition and grow, evolve our inspirations and our desires. If you look at it in this context, that puts architecture at a very important position in our culture. And, you know, we have many different types of buildings now, but really if you look at them closely and kind of dissect them, you can trace their roots back to many of these fundamental human desires and institutions that Kahn was describing. So, even in our contemporary society with hundreds of different types of buildings, but you can see all that they are, you know if you break them down lots of them can be traced back or many of them, most of them can be traced back to these, our most fundamental desires. So, Khan felt that inspiration was fading within people in our culture and he feared that institutions would perish if humans can’t connect with and feel their inspiration and inspiration and their sense of being. Architecture was the structure that housed these institutions and thus served as the, again, midwife of inspiration. Therefore, architecture had the unique capability to reignite inspiration within our culture. If you, again, if you pose, if you put architecture in that light, the buildings that are in our cities and that we inhabit on a daily basis plays such a vital role in helping us to develop as humans and helping us to answer these most fundamental questions about our lives and distilling our purposes, our essences, our energies to what really matters. That's a brief overview of Kahn's spiritual philosophy. You can get much more information on that in several books that John Lobell has written on Louis Kahn. One is Architecture as Philosophy and the other would be Between Silence and Light. I had the privilege to speak with John recently about Louis Kahn and about his experience with Khan when he was at was at Penn, and really fascinating discussion. But again, John, many of these thoughts that are being presented here are coming from John's books and the discussion that I had with him. So, I would recommend going back to reference some of his online lectures and his books if you're interested in getting more into that.

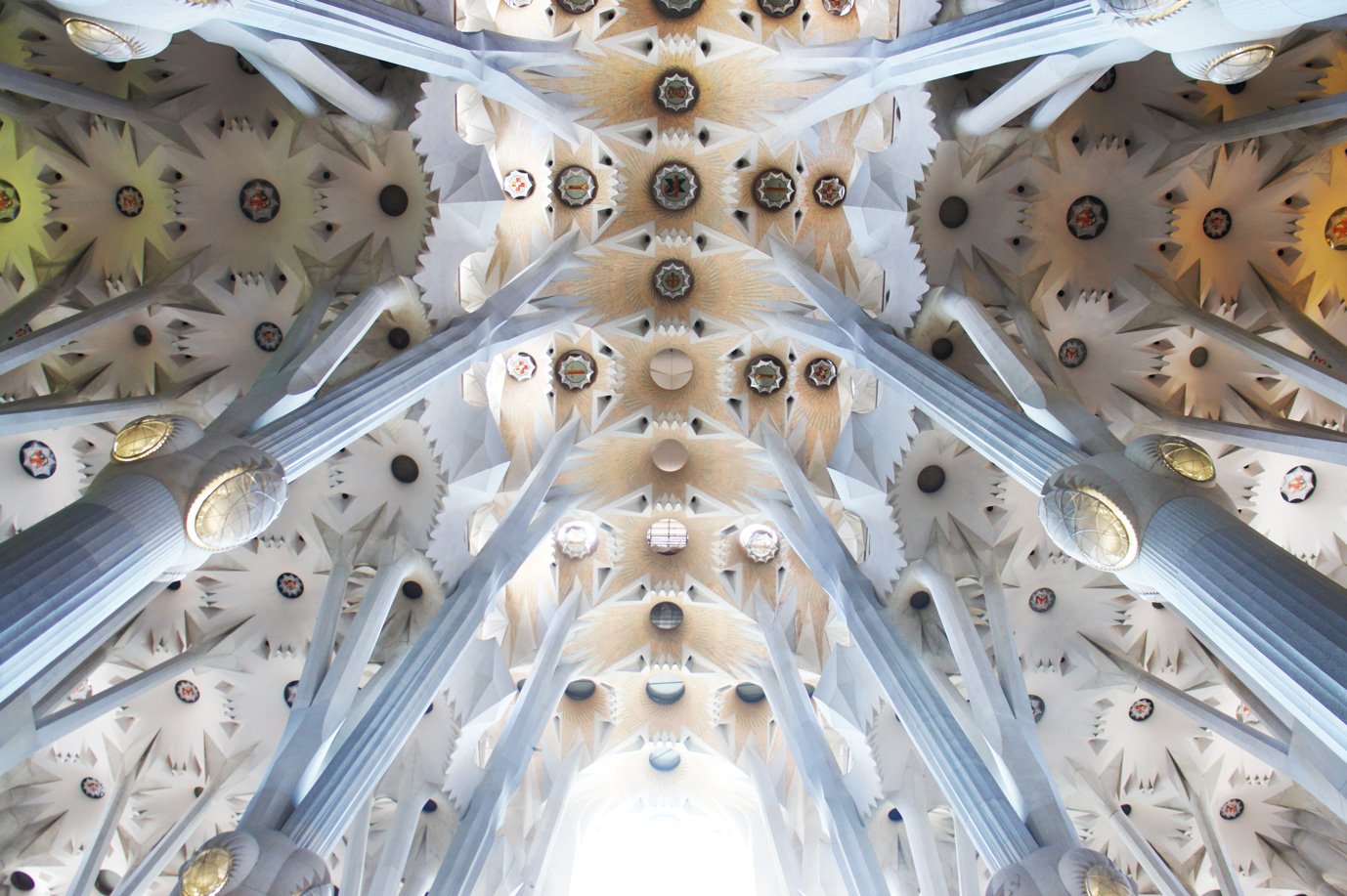

You can see the degree of depth that Khan thought about architecture. This was not just a professional endeavor for him. This was not a career for him. This was a deeply spiritual endeavor for him that really touched at the roots of our human existence. And Kahn thought about it that way and he put that type of intensity and thought into his work. So, he sought to evoke the immeasurable in buildings. So, although necessary tasks in architecture, such as the program, the site layout, the budget, all these things were in all of his projects, he took them seriously and kind of ticked the boxes, but he sought to evoke something communicate something much, much, much deeper in his buildings. And he called that kind of the immeasurable. He famously kind of asked the question, "Building what do you want to be?" When he kind of came upon an answer to that question, again he called that the immeasurable, the essence of the building, he knew that architecture was a physical process of manifesting a physical building into this world. And what he said is he needed to derive the immeasurable and derive the essence of the building, ask the building what it needed to be, but then he also needed to have the skill or the architect needed to have the skill to take that idea of the unmeasurable and bring that through this kind of pragmatic process of the real world. So, things such as design, drafting, permitting, agency approvals, client budget, he recognized that and he called that the physical realm or the realm of the measurable. So, you need to take a building from the unmeasurable to the measurable. But then when the building was completed, it needed to return to the state or expressed this idea of the immeasurable. So, he viewed, I believe his role in some ways as the architect to kind of protect that immeasurable essence of the building through the, did these kind of pragmatic processes necessary to bring the building to fruition in the real world. And I think he took that very seriously. I think you know, relatively good at it and understood that. But it was this ability to shift between those two worlds that allowed him to build these buildings. You know, he knew that he had to have a deep essence of the spiritual and measurable qualities to a building. And then also he knew that he had to, you know, put on his more pragmatic hat and get the thing built. But then at the end of the day, His buildings were, many of his buildings were able to and still do, the ones that exist are still standing. He was able to, they communicate the sense of the immeasurable and you can feel that. I've had the opportunity to go into many Kahn buildings and you can definitely feel the power behind them and it emotionally evokes something in you. And I've made the comment before that, you know, you go into Kahn’s, let's say, you know, the Salk Institute in San Diego and in you’re, it's a laboratory you think you're gonna go into a science laboratory, and it feels much more like a religious building than a laboratory and I think that's the quality that many of his buildings have in the British Art Center in New Haven, Connecticut, I think that also has a very similar feeling. You go in there and you think you're gonna go to a museum, an art center, and you really feel like you're a bit in a spiritual cathedral of some sorts. But so it's a unique and interesting feeling that you, or at least that I experienced going into some of his buildings.

For me, Khan's buildings transcended stylistic trends or functional pragmatism. They offer profound experiences, eliciting a sense of timelessness, solidity, and repose to their very quiet buildings, but solid at the same time. Again, I'd recommend anybody interested in Khan to go and read John Lobell's books on him and then we have an article on our website about the philosophy of Khan as well with some photographs of the different buildings that I've been fortunate to visit of Khan's so I hope you enjoyed and thanks for listening.

Reflecting on what a city's layout and its most prominent buildings portray, Principal and Architect of ROST Architects, Mitchell Rocheleau, discusses what impact he believes this has on the values emphasized by a city and how this affects the human experience.