The Story of Frank Lloyd Wright's Oak Park Home and Studio

Watercolor painting with post processing of Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio by Mitchell Rocheleau. Image Copyright 2024 by Mitchell Rocheleau

I visited Frank Lloyd Wright's home and studio in Oak Park, Illinois on a frigid January morning. Seeing where Wright started and grew his practice added clarity to the story of one of America’s greatest architects. The Home and Studio were the breeding grounds for a new modern American Architecture. Many ideas that shaped the profession came from this tiny home and studio on the outskirts of Chicago.

The home and studio were an ongoing project for Wright, constantly developing, and being added to. He used it as a testing ground for his ideas, details, and architectural philosophy. The structure is an amalgamation of four additions completed between 1889 and 1911.

The Original Home

In 1889 Wright purchased a small plot of land with his to-be wife, Catherine Tobin. He was loaned the money from his employer, renowned architect Louis Sullivan. At the time, Wright was a young architect, unknown in the profession, trying to advance his career and raise a family.

He designed a small compact two-story home organized around a central fireplace. The house had a typical gable roof, shingle siding, and a conventional layout. The house was modest in its original form. Over time, Wright installed eclectic decorations, detailing, and art. There are Greek sculptures, Japanese paintings, Chinese furniture, and paintings inspired by Arabian Nights.

The original home featured stained glass windows, leaded art glass skylights, geometric patterns on walls and ceilings, decorative fireplaces with intricate tile work, custom furniture designs made specifically for each room, including chairs with curved backrests inspired by Japanese aesthetics, and many other innovative elements never before seen at that time. The design also incorporated natural materials such as brickwork from nearby lakeshore bluffs and limestone quarried near Chicago's Garfield Park Conservatory.

To pay for the ongoing construction and support his growing family, Wright would take on jobs outside his regular employment at the offices of Adler and Sullivan. Once the firm learned of his outside endeavors, they would part ways, and Wright would set out on his own. He set up a small office in Chicago that he would work out of for the next few years.

The Kitchen and Playroom Addition

In 1895, with a growing family, Wright decided he needed to add to his home. He added a wing with a kitchen and maids’ quarters on the first level. On the second level would be the playroom for his children. The playroom was a space where he experimented with his developing architectural ideas. It has a high barrel-vaulted ceiling, with low windows on each side. The windows are set only about 2 feet off the floor with integrated bench seating, perfectly sized for children.

There is a built-in piano, mezzanine, and library with a large fireplace on the wall. Over the fireplace is a large mural of a fisherman and genie from the Arabian Nights painted by Charles Corwin, a local Chicago artist. A massive skylight allows natural light to flood into the space. Wright had a keen interest in child development and designed the playroom specifically for them. He believed that spaces could profoundly impact a young person’s development and imagination.

The Studio Addition

His small practice grew quickly, and he decided to build a studio addition to his home. The architecture of the studio addition is noticeably different from the original house. It illustrates a departure and maturation from the architecture of the original home. The architecture of the studio addition does not use a gabled roof or attempt to blend with the original home. Instead, it has flat roofs with rectangular and octagonal-shaped forms. The materials used in the addition were similar to the original house, however, the detailing and trim work on the facades is noticeably different.

The studio addition contained a terrace, loggia, reception hall, drafting room, central office, and library. The drafting room is two-story with a balcony overlooking the drafting area below. The library is octagonal in plan, along with the second level of the studio.

Like many of Wright’s buildings, the entry procession is dynamic and memorable. The entry to the studio is on Chicago Avenue, which you access via an elevated terrace. A series of columns on the terrace leads you into a low-covered loggia. The columns forming the loggia appear to be made from cast iron. However, they are created with plaster and painted to appear as iron. From under the loggia, you can access the lobby of the studio.

Once inside the building, you can go left to the studio or right to the library. In the entry, the detailing, lighting, and woodwork are remarkable. The spaces are powerful and full of intricate detailing. I imagine this space was designed to make a profound impression on first-time clients. Without saying a word, Wright used his architecture to communicate and showcase his abilities.

The two-story drafting room is the primary feature of the studio. A series of chains hang a balcony from above, creating a workspace for artisans and sculptures that looks down into the drafting room. On the balcony, the plan transitions to an octagonal shape and is surrounded by windows. The windows provide the second level with natural light for working and flood the double-story volume with sunlight.

At the time, fires were a huge concern. In the evening, the drafting technicians and artisans were required to roll up their drawings and put them in a plan holder to be stored overnight.

Many talented young draftsmen and apprentices would come through the studio. He would design nearly 125 buildings while working in the Oak Park studio. This would satisfy the desire to integrate life and work together. This was a theme that Wright would follow for the rest of his life and be repeated at his Taliesin studios in Wisconsin and Arizona.

Wrights’s career and family life would be tumultuous. He would go through many highs and lows. Several years before his death, he returned to the Oak Park home. The property evoked feelings of nostalgia and frustration for him. In his eyes, the home exposed the naivete of a young, struggling architect.

Front Elevation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home and Studio in Oak Park Illinois. Image Copyright Mitchell Rocheleau

The Home and Studio Today

Upon arriving at the house, my first impression was that the exterior architectural form was uncharacteristically disjointed and unrefined compared to Wright's other work. I was critical of this apparent lack of architectural cohesion.

However, after touring the home and learning that the house was a product of multiple phases of work, I gained a new understanding and appreciation for the home. The amalgamation of disjointed parts told the story of a young architect developing his ideas, raising a family, and building a career. This was relatable in many ways and something I could appreciate on a much deeper level.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Trust decided to restore the house in 1974. The restoration would return the home to its state in 1909, the last year it served as a functioning office. The renovation took thirteen years and cost nearly 3.5 million dollars. Over the years, the home and studio have continued to be popular tourist destinations for visitors worldwide.

We hope that you enjoyed the story of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Oak Park home and studio.

References:

Abernathy, Ann, and John G. Thorpe. The Oak Park Home and Studio of Frank Lloyd Wright. Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust, 2010.

Elevation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home and Studio in Oak Park Illinois. Image Copyright Mitchell Rocheleau

The ceiling of the Second Level Playroom in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home and Studio in Oak Park Illinois. Image Copyright Mitchell Rocheleau

Entry terrace and loggia of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Studio in Oak Park Illinois. Image Copyright Mitchell Rocheleau

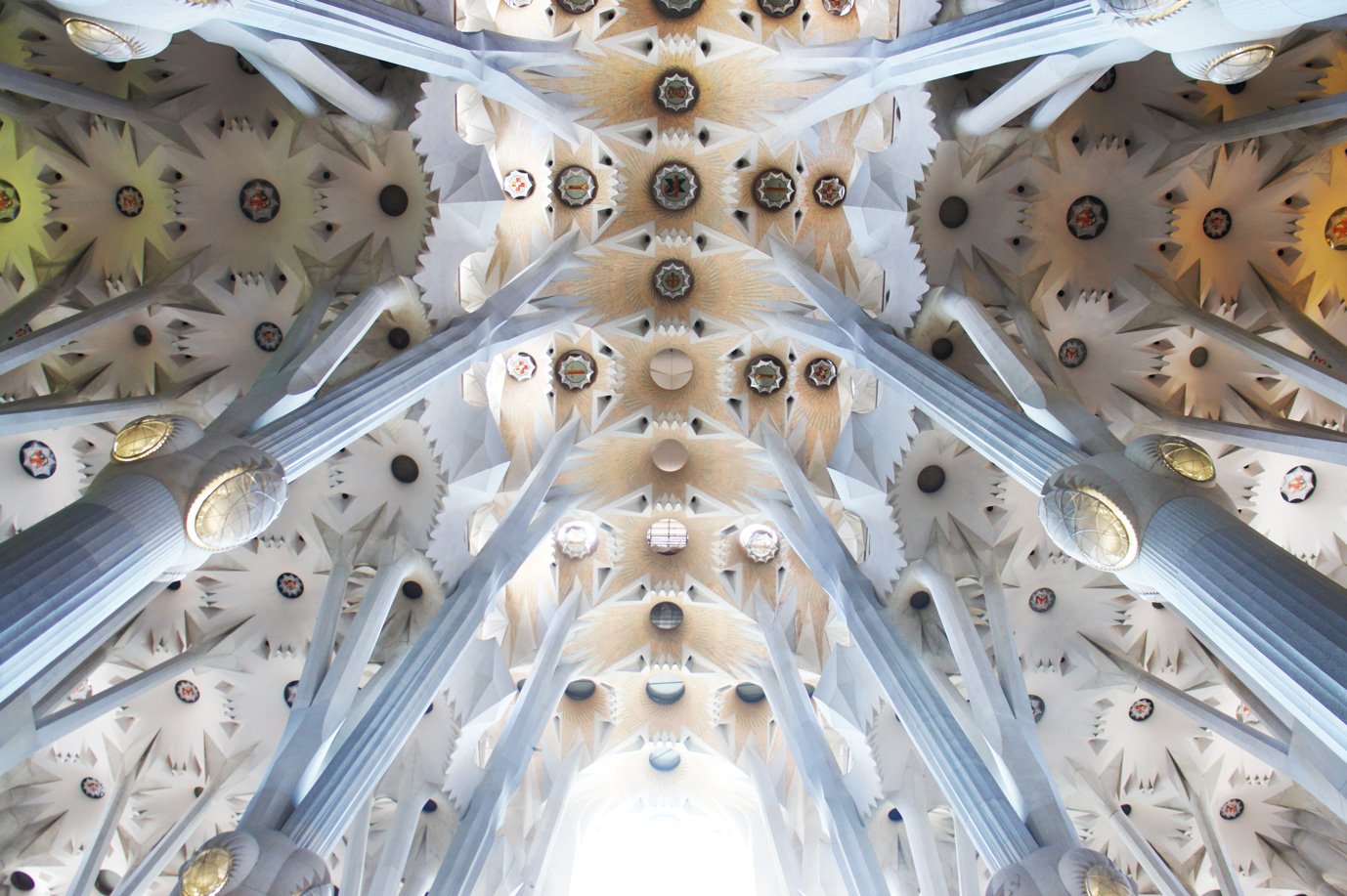

Stained glass ceiling in Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio in Oak Park Illinois. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Double-story space showing the suspended balcony inside the drafting room of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Studio in Oak Park Illinois. Image Copyright Mitchell Rocheleau

Entry lobby at Frank Lloyd Wright’s studio. Image copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Front Elevation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home and Studio in Oak Park Illinois. Image Copyright Mitchell Rocheleau

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home and Studio in Oak Park Illinois. Image Copyright Mitchell Rocheleau

Front Elevation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home and Studio in Oak Park Illinois. Image Copyright Mitchell Rocheleau

Front Elevation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home and Studio in Oak Park Illinois. Image Copyright Mitchell Rocheleau

Principal and Architect of ROST Architects, Mitchell Rocheleau, discusses the significance of The Grand Louvre designed by Architect I.M. Pei, the history of the Louvre, design process, design theory and ideas behind the project.