The Story of the Florence Cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore

Watercolor of the Florence Cathedral by Mitchell Rocheleau. Copyright 2024

Santa Maria del Fiore, also known as the Duomo of Florence, is an iconic architectural landmark in the Tuscan capital. It is a stunning masterpiece of architecture and stands as one of the most recognizable buildings in Europe. The great dome that covers the structure was designed by Filippo Brunelleschi and completed in 1436 – making it one of the oldest domes still standing today.

I traveled to Florence specifically to see the Cathedral. Before visiting, I wanted to see the Cathedral's scale within the city's context. I walked south from the train station and crossed the Arno, the large river that runs east and west through the town. After crossing at the Ponte alle Grazie, I hiked up the hill to Giardino delle Rose. There was a lookout point where you could look north across the river and see nearly the entire city. The Cathedral is nestled within the urban fabric, soaring high above the rooftops. The scale was unlike anything I had seen before. Above is a photograph from this vantage point.

The next day, I got a cup of coffee in the Piazza del Duomo and tried to absorb the architecture. Before entering, I wish I had better understood the rich and complex history behind this building. Only after my visit did I dive deeply into its past and how the building came to fruition. It is a story worth hearing.

Florence Cathedral, Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

THE BEGINNINGS OF SANTA MARIA DEL FIORE

Before the structure we see today was constructed, there was an old church called San Reparata. At the time, Florence was growing into a major city in Europe. Its wool and banking industries were flourishing, and some of the most luxurious cloth in Europe came from Florence. The financial success catalyzed a re-awakening of arts and architecture. Wealthy merchants and guilds would begin investing money in many buildings, including monasteries, palaces, and churches. A building boom of this sort had yet to be experienced since the Roman Empire.

A group called the Wool Merchants Guild would organize the construction and financing for a new Cathedral to replace San Reparata. The Guild organized a group called the Opera del Duomo, which would oversee the Cathedral's construction. Because their expertise was in wool and textile manufacturing, not in construction and architecture, they decided to appoint a capomaestro or head architect for the project. Throughout the construction of the Cathedral, which spanned nearly two centuries, there would be many different capomaestros on the project. The history of capomaestro was riddled with instability, rivalry, betrayal, and corruption.

Construction would begin on the new Cathedral in 1296. The first Architect or capomaestro for the project would be Arnolfo di Cambio - a renowned architect and sculptor at the time. Unfortunately, he would only work on the project for six years before passing away in 1302. It is unclear how much of his original design intent was actualized.

Large areas of the existing urban fabric would need to be demolished to build the Cathedral. Homes, shops, and roads would be torn down to accommodate the massive structure. Many of the existing streets and paths would need to be re-routed for the new Cathedral.

THE CAMPOMAESTROS and the 1366 Model

There were several capomaestros that worked on the project after the death of Cambio. These included Talenti, Giovanni Ghini and Brunelleschi.

In 1366, completion to submit models for the Cathedral was requested again. Ghini and Talenti's son Simon both submitted proposals but were rejected. The judging board presented a model, which was accepted as the final design moving forward. All subsequent capomaestros moving forward would be required to pledge allegiance to this model.

The design of the dome in the 1366 model was to illustrate the shape and scale only. The constructability and engineering requirements to create the dome would be overlooked. It would be a problem left for future capomaestros to solve.

Florence Cathedral, Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

THE MISSING DOME

Construction progressed for several decades, and the Cathedral rose up from the earth. However, there was one problem, it was missing its signature dome. For nearly 50 years, no one was able to develop a plan to construct the dome according to the original design model. Many people thought it was an impossible feat.

There were several challenges with constructing the dome. The first was to build the dome without any wooden centering or scaffolding to support it during construction. The quantity and size of the timber members required to construct centering for a dome of this scale would be massive. For this reason, the Opera requested that the dome be built without centering.

The second challenge was to construct the dome without external buttressing. Buttressing is the addition of external supports outside the structure to counteract the dome's horizontal thrusting forces. Buttressing was commonly used in Gothic Cathedrals in France and northern Europe. Cathedrals such as Notre Dame in Paris and the Duomo in Milan utilize buttressing. The Florentines were sternly opposed to mimicking the architecture of these regions.

In 1418, the Opera del Duomo held a competition hoping to solve the problem of the dome finally. The applicants were to submit technical and realistic solutions to construct the dome, as shown in the model from 1366. The winner of the competition would receive 200 gold Florins.

A 41-year-old goldsmith, Phillipo Brunelleschi, would submit a model with a clever solution. His solution would be self-supporting during construction, not requiring any centering or buttressing, and achieving the design model's look. He would win the competition. Unfortunately, only some of his drawings or documents describing the construction are left.

Florence Cathedral, Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

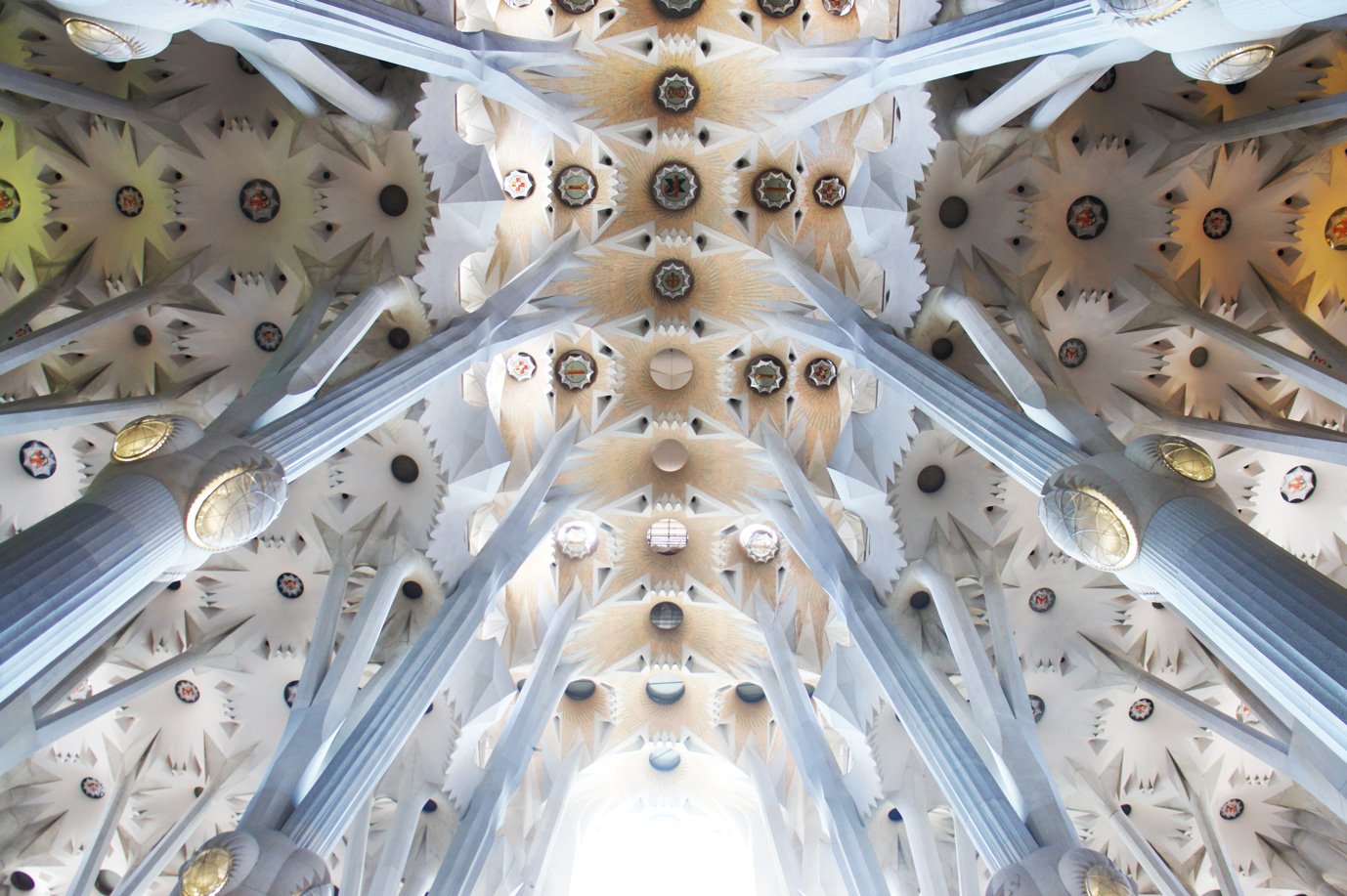

Florence Cathedral Interior Dome, Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

THE EARLY YEARS AND TRAINING OF BRUNELLESCHI

Brunelleschi grew up next to the half-built Cathedral. He undoubtedly watched the structure's construction and became enamored with the construction process. As a young man, Brunelleschi became a master goldsmith. He would enter the competition for decorative bronze plates on the Baptisty next to the Cathedral. A group of 36 judges would determine the outcome of the competition. The artists were given one year to complete their submissions. Brunelleschi and Lorenzo Gilberti would be the two finalists. This event would begin a lifelong rivalry between the two men. The two men were asked to work together on the five panels. However, Brunelleschi denied it and started his journey exploring architecture.

After the competition for the Baptistry doors, Brunelleschi would travel to Rome to study the ancient architectural ruins. He would survey different building sites and sketch and learn how the Romans built. This trip would be inspirational for his development as an architect and prime him for his return to Florence. Upon hearing of the competition for the Dome of the Cathedral, he would immediately travel back home armed and educated from his travels, ready to begin his legacy as one of the greatest Florentine architects.

Florence Cathedral, Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

BRUNELLESCHI'S SOLUTION FOR THE DOME

Brunelleschi would design a double-shell dome. The two shells served different purposes while also operating together. The exterior shell would be an eight-sided vaulted dome that would achieve the height and shape that the Opera demanded.

The inner shell would serve multiple purposes. From the inside, it mimicked the form of the eight-sided vaulted dome but on a smaller scale; however, this shape was purely cosmetic. The inner dome was a complete hemispherical dome at its structural core. Brunelleschi needed the hemispherical dome because it is the only dome shape that can be erected without centering or scaffolding which would satisfy the Opera's demand to eliminate centering.

With the use of a hemispherical dome comes the issue of lateral thrust. A hemispherical dome produces more lateral thrust than the eight-sided pointed vault. To counteract the lateral thrust, Brunelleschi used a series of compression rings around the dome's circumference. This held the dome together, similar to a belt on a pair of pants.

Eight massive wooden ribs follow the curvature of the octagonal pointed dome, combined with a series of horizontal wooden and metal rings that would act as compression belts around the dome's circumference. These belts would help prevent the dome's outward thrust through buttressing or massively thick drum walls. This created a lightweight internal structure that reduced the overall weight of the dome, thus reducing downward compression on the drum.

To assist with the horizontal thrust, he also implemented a unique brick pattern within the shell of the inner dome. He used a herringbone pattern which gave additional resistance against outward thrust.

The two shells were then joined together with a series of wood ribs with a large void between the layers. This would make the two layers act together as a single structural system while drastically reducing the home's overall weight.

The space between the two dome shells, shown in the image below, acts as a stairwell to the lantern on top of the building. From the lantern, you can get panoramic views of the entire city. Although it is a long climb, it is worth every step.

View inside the void between the two shells of the Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. This stair leads to the lantern on top of the cathedral. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

The much-lauded dome was designed by Brunelleschi in 1420, although his initial plans were not approved until 1436 when construction began. By 1436, construction had finished on one of Brunelleschi's most remarkable architectural feats - and arguably one of Italy's most recognizable landmarks.

Remarkably, Brunelleschi solved many different problems within the two-layered dome structure. Throughout construction, he faced technical, political, financial, aesthetic, and personal challenges, which he navigated through to complete the dome.

Florence Cathedral, Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

THE BELL TOWER - CAMPANILE

Next to the Cathedral is the 280-foot-tall Campanile or bell tower. Often overlooked in the history of the Cathedral, the tower is a landmark and a complex feat of engineering in itself. The tower was completed in 1359, taking nearly two decades to finish. The Campanile sits on the southwest side of the Cathedral. It is rectangular in plan with octagonal buttresses on all four corners. It has graduated orders with the heaviest at the bottom and reducing visual and structural weight towards the top. There are openings towards the top that allow for the operation of the bell tower.

View from the top of the dome of Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

THE BAPTISTRY - SAN GIOVANNI

Like the Campanile, the Baptistry does not receive the attention it deserves. The Baptistry was the principal religious monument and preeminent symbol of faith in Florence before the Cathedral was built. The structure is octagonal in plan with a projecting apse to house the altar. Inside is a massive volume, with the lower portion of the drum being distinctly Roman. The interior proportions and dimensions are derived from the Roman Pantheon. The early history of the Baptistry has yet to be discovered. There are theories that there was once an old Roman temple built in this location. There were excavations made that uncovered foundations dating back to the Romans.

In 897 AD, some documents record the Baptistry on site. The Baptistry was reconstructed in 1059 by Pope Niccolo II. Although we don't know exactly when the structure was clad in its white and green marble skin, it most likely occurred shortly after the reconstruction. The dome of the Baptistry is 85 feet in diameter. Although the inside of the structure references the Pantheon, the dome is different in that it consists of eight curved segments instead of a coffered system.

The competition for the Baptistry doors was a momentous event that helped to introduce Brunelleschi to the construction of the Cathedral. Although ultimately unsuccessful, it left a chip on his shoulder to prove himself later in life with the dome's design.

Baptistry Bronze Door Plates, Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Baptistry Bronze Door Plates, Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Baptistry Bronze Door Plates, Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

CRITICISM of the Florence cathedral

It cannot be denied that the Florence Cathedral is a masterful work of engineering genius. Its scale, craftsmanship, and ingenuity are impressive. However, with a structure, this large, my expectation for the space created inside was very high. Unfortunately, the atmosphere and interior space of the Cathedral were underwhelming. The inside appeared dark and dingy with insufficient natural light, especially at the human scale.

It seemed that the Cathedral fell victim to a classic architect’s syndrome which is to put all the emphasis on the exterior form, materials, and engineering of the building while letting the interior spaces be an afterthought. The exterior detailing on the building is far more intricate and beautiful than the interior.

Although the design objective was to eliminate buttressing (a technique used in Gothic Cathedrals to allow for larger openings), there must have been another way to allow more natural light into different parts of the building.

This may have been exacerbated by the seemingly flat and dull interior finishes in the Cathedral. Throughout the vaults and walls, there is a single flat plaster finish. It is understood that this was the aesthetic trend of the time. However, the overall effect of the interior spaces was insufficient, given the stature and intent of this Cathedral.

Florence Cathedral Interior, Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

CONCLUSION

In addition to being an iconic landmark in Italy, Santa Maria del Fiore has become an integral part of the Florentine culture and economy. Santa Maria del Fiore is more than just another cathedral or religious building but instead serves both spiritual and aesthetic purposes, thus making it a truly unique place worth visiting if you ever get a chance to do so. With its intricate details crafted by some of Italy's greatest minds throughout history - combined with spectacular views over Florence - there's no denying why this majestic building continues to draw millions of visitors year after year.

Florence Cathedral, Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. Photograph copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

References

Goy, Richard John. Florence: The City and Its Architecture. Phaidon, 2006.

King, Ross. Brunelleschi's Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture. Bloomsbury, 2013.

Principal and Architect of ROST Architects, Mitchell Rocheleau, discusses the significance of The Grand Louvre designed by Architect I.M. Pei, the history of the Louvre, design process, design theory and ideas behind the project.