Early History of Cities and The Development of the Urban Form

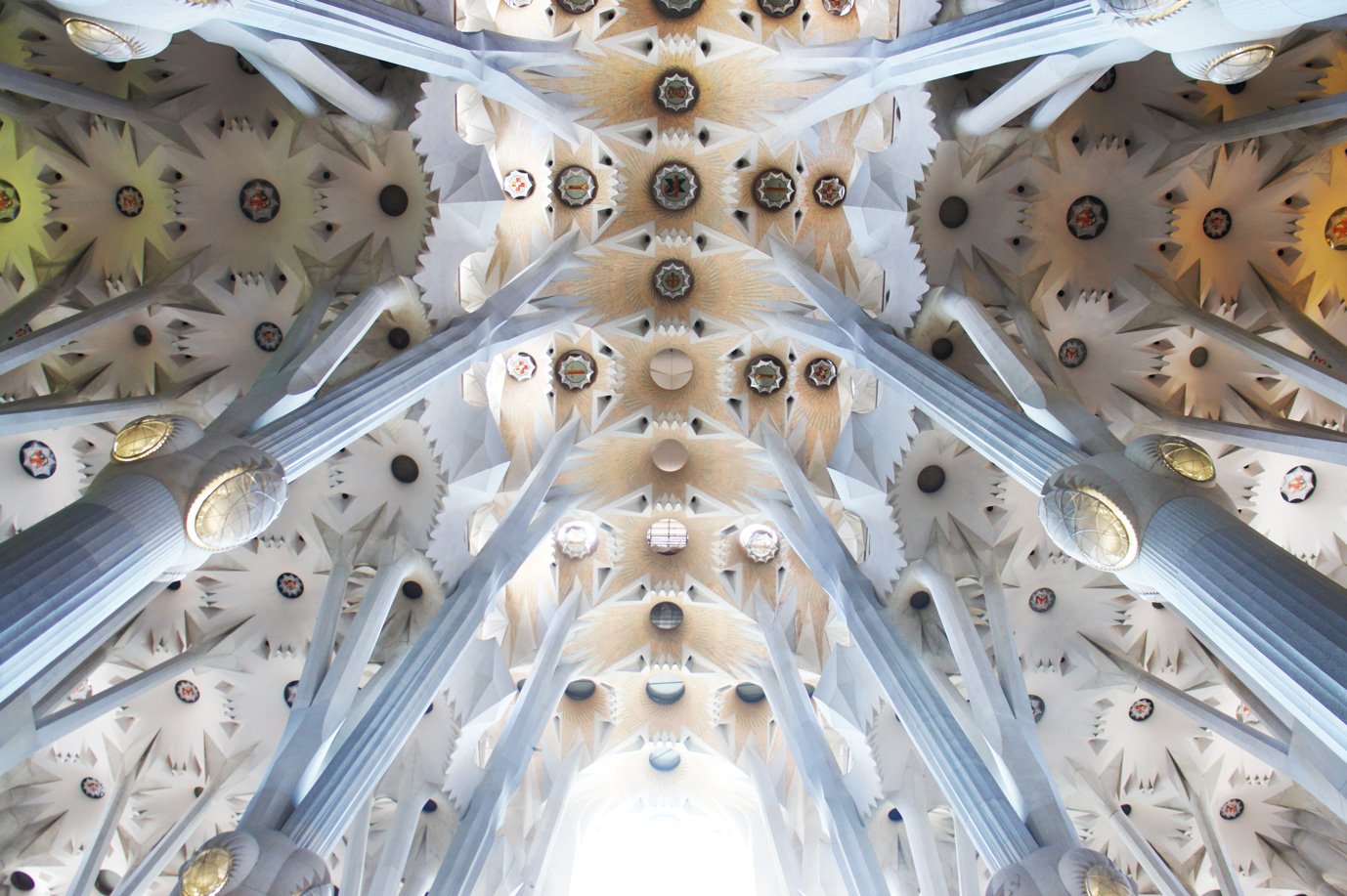

High-angle view of the Great Ziggurat of Ur, ancient Mesopotamian site. AI interpretation intended for visualization purposes only.

How did cities develop? Many of us take our environments for granted without questioning how and why they evolved into the forms we see today.

In his book The City in History, Lewis Mumford provides a fascinating account of the history of cities. His interpretation dissects the complex forces that led to their creation. He discusses what forms these forces manifest themselves in throughout history.

Investigating the history of cities will help us understand how we got to this point and why our cities look the way they do. Through this exploration, I hope to uncover insight, context, and a foundation for designing future cities. Are the physical, social, and economic forces that our cities were built on still optimal and relevant today? If not, how can we rethink the city and provide optimal environments that support the values of our contemporary culture?

Early Nomadic Humans

Early nomadic humans established geographically fixed gathering locations that they would periodically visit. These locations were used for rituals, burial grounds for the dead, places for protection, places to make art, and places for seasonal pilgrimage.

As these meeting grounds became more established, their acceptance spread and were shared to other groups. They became embedded in their culture and spiritual practices and acquired more meaning. Semi-permanent shelters and camps began to develop nearby. Increased communication, cooperation, and the domestication of plants followed. Familiarity, dependency, and tradition with these meeting grounds led to the early formation of small semi-permanent villages.

Establishing More Permanent Settlements

Establishing more permanent settlements was conducive to childbirth and raising. It increased the chances of survival for the young. A slower, more cooperative, and nurturing lifestyle would have flourished. This environment prompted the technological innovation of the vessel.

The Vessel

The vessel was a pivotal technology in the city's development. It allowed people to store food and transport water, which promoted the growth and viability of these more permanent settlements. Vessels were made from mud, clay, and woven vegetation. Perhaps shared amongst the community, larger vessels in the form of granaries would have been built to help provide food reserves for challenging and unpredictable shortages.

Through these smaller innovations, larger-scale advances such as the irrigation ditch and drains would have stemmed. Shaping the earth through clay, mud, and water was integral to shaping the city. With irrigation ditches, larger plots of land could be cultivated, offering more predictable water supplies.

Attentiveness to childcare, plant care, control of water and vessel crafting would have shifted the nomadic tribe's anxious, unpredictable, and mobile lifestyle towards a more stable, geographically fixed, and predictable existence. It would have fostered a sense of foresight and continuity that yielded increased assurance of the future. This would relieve some of the feeling that man was at the mercy of nature and the world, giving them greater control, thus granting hope and optimism for the future days.

Establishment of the Chieftain or King

As these small villages grew, leadership and decision-making became important. At this moment, the masculine hunter role made a resurgence after many years of dormancy during the era of the peaceful small domestic village. During this time, the hunter would have become discontented with the highly repetitious, unadventurous daily life of the domestic agricultural lifestyle.

Mumford argues that settlements should be described as villages rather than cities before the chieftain emerged. Only when a chieftain, leader, or eventually king is established do cities, as he defines them, begin to emerge.

City and its Accumulation of Embodied Energy

With increased growth and accumulation of resources, valuable food stores, tools, and other artifacts lured interest from outside of the village. Driven by outside threats, the king searched for protection methods. At this point, the city evolved into a container, with its primary function being a storehouse to protect its accumulated possessions.

It was a storehouse for food, materials, people, knowledge, religions, customs, technology, and ideas. It contained much-embodied energy capable of being directed to other tasks beyond survival. As more energy was stored, a surplus of resources and time became available, providing fertile grounds for innovation.

Development of Records and Art

Records, glyphs, scripts, and monuments developed around this time. They represented and recorded activity, status, and events. Some of the best records came in the form of buildings. They told the story of the ruler who built them, their prestige, and the values for which they were built.

Art creation on a smaller scale was also a byproduct of the city's embodied energy. Now, each generation could leave a log of its ideal forms and images for future generations. This came in the form of statues, portraits, paintings, and crafts. These artistic outlets allowed humans to satisfy their desire for immortality. The artifacts were made of stone, and their messages and ideas would be passed down for many generations.

Built Environment as Symbols

In the ancient city, the place of worship, such as the temple or shrine, merged with the place of rule, the palace. This two-headed organism created a system of ruling that still prevails today. The physical monuments that housed these two functions often dominated the form of the ancient city. Their primary purpose was expressing power, giving the city a definite, identifiable form.

Walls or fortifications surrounding the city also gave cities a distinct form and were symbolic. The wall created a clear and distinct boundary between the city and the countryside beyond. It separated the two worlds and gave identity to inside vs. outside people.

The city radiated symbolic power through the edification of the temple, palace, and wall. Its rulers received tribute and riches from those seeking approval, support, protection, and acceptance. This reciprocal relationship enabled the generation and often exploitation of large amounts of wealth for those in power.

Specialization of Workers

The specialization of workers would have developed within the early city. Before this, humans were unspecialized, learning an array of skills and adaptations to survive in nature. Various skills, knowledge, and technologies would have been passed down from ancestors, which ancient humans may have gravitated more strongly towards compared to others. However, complete dedication and specialization of a single skill were most likely impossible for survival.

With the advent of the city and the hierarchy established by the king, labor tasks started to become divided. This benefited the king because it organized labor and ensured maximum production and efficiency in producing goods. Although this may have been in service to the king and the city at large, I would argue that it was detrimental to the individual and the long-term prosperity of the population. It would create a unidimensional person with a contracted view of the world who lacks depth, richness, and a variegated sense of balance in their daily lives.

Specialization primarily occurred amongst the working class, and the ruling class maintained the ability to pursue various interests, occupations, and pursuits. The goal for the ruling class was to create a social machine where, through the standardization and specialization of labor, people were replaceable in an economical production. The specialization of workers helped to create abundance, predictability, and safety within the city. The lower class quickly identified the system's advantages, thus a general adoption of the lifestyle. However, the long-term negative effects on the individual were more difficult to predict.

Mumford notes, "Biologically man had developed farther than other species because he had remained unspecialized- omnivorous, free-moving, handy, omnicompetent, yet always somewhat unformed and incomplete, never fully adapting himself to any one situation…” (Mumford 106).

City and Occupation as Identity

Although the realities of the common citizen were often bleak and exploitative, they were an improvement from life outside of the city walls. People embraced living in the city and it became part of many people's identities. They developed personalities that defined their occupational specialties such as baker, farmer, or blacksmith. The development of the King would have been the grandest personality.

Often, the ruler of a city would become wrapped in self-delusion, confused, and convinced that he obtained divine powers and rights. Everyone became a character in the urban theater, each playing their role. This created a collective illusion where the king acted to maintain power, control, and wealth. The citizens played their role in maintaining the king's safety, allegiance, and protection. Each one needed the other to keep the system running.

This arrangement produced tangible progress, innovation, and growth through predictability and rules. Cities cultivated humans' capability to tell stories. We operate within these stories collectively through mutual trust. In this arrangement, we have made many beautiful advancements. Simultaneously we now know that overadherence to our personas, often results in depression, anxiety, and dissolution of the individual.

Innovation from the Palace

Many innovations in early cities resulted from the early rulers' concentration of wealth and power. Innovations such as drains, running water, bathtubs, private sleeping quarters, and toilets all came from the palace. With both the available funds and the will to improve their lifestyles, innovation resulted. This phenomenon continues today with the research and development divisions of large corporations. Their excess wealth can be directed towards innovation to produce more or better products/services. This grows the economy, and over time, the products/services developed trickle down and become available to the public.

The City, Sacrifice, and Collective Human Development

Perhaps unknowingly, the ancient city created an ecosystem that gave a chance to a limited few to achieve maximum development potential. They were able to thrive, create, innovate, and solve higher-level problems. This opportunity was given through the sacrifice of working-class citizens, whether voluntary or forced.

The citizens generated a surplus of food, wealth, stability, and protection. With their basic needs met, their energies could be focused on solving other problems. Innovation and progress could now be made. Over time, this progress trickled down into society, fostering slow and steady collective advancement.

Without the city's formation and the working class's collective sacrifice, progress would have been limited as everyone would have been occupied with their daily struggle for survival. Mumford describes this phenomenon by stating, “In the end, the city itself became the chief agent of man’s transformation, the organ for the fullest expression of personality.” (Mumford 110)

Conclusion

I've described the city's foundational makeup up to this point in history. Although the city has evolved markedly beyond this point, it still has traces of these ancient principles deeply embedded in its DNA. I urge us to revisit these principles, structures (physical and mental), and ideas about our cities to assess whether they are still serving us.

If the city is our most powerful mechanism for fostering man's transformation and collective human development, is the mechanism calibrated to aim at the right goals and values?

Bibliography

Mumford, Lewis. The City in History: Its Origin, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. Penguin in Association with Secker & Warburg, 1966.

Principal and Architect of ROST Architects, Mitchell Rocheleau, discusses the significance of The Grand Louvre designed by Architect I.M. Pei, the history of the Louvre, design process, design theory and ideas behind the project.