The Story Behind the Architecture and Construction of the Roman Baths in Bath, England

Photograph of the Great Bath at the Roman Baths. Photograph by Mitchell Rocheleau. Copyright 2025

I want to take you on a journey back in time in the southwest of present-day Britain, near a bend in the River Avon. Here, a natural geological process has dispelled warm, mineral-rich water from deep within the earth for thousands of years.

The ancient people who inhabited this area believed these healing and mystical waters were a gift from the gods and were presided over by an ancient goddess named Sulis.

Since then, the people in the area have coveted the mystical waters, which attracted people worldwide. This is the story of how these hot springs influenced the course of history, facilitating the growth of a small settlement that ultimately led to the growth of a unique cosmopolitan city in the southwest of England, named after its healing waters. This is the story of the Roman Baths in Bath, England.

The Natural Hot Springs and Its Prehistoric People

The natural hot springs near the River Avon have been considered sacred for thousands of years. Here, at the southern end of the Cotswolds, in Somerset County, in Southwest England, our prehistoric ancestors gathered to bathe and conduct ceremonies at the hot springs. Archeology suggests evidence of settlements around the springs from about 600 BC.

Celtic Iron Age people, called the Dobunni tribe, inhabited the area. A stone wall and an outcropping constructed of gravel and rubble discovered in the spring suggest these people were using the waters for bathing and religious ceremonial purposes. The outcropping would allow them to walk farther into the waters to conduct rituals and ceremonies. In 1979, excavators also found Celtic coins from the Doubunni tribe, at the bottom of the spring.

To them, this site undoubtedly must have exhibited supernatural powers. These early people would have seen the warm steam rising off the water's surface when it was first discovered. The warm water would have had a slight sulfuric smell and orange-red coloration, just as it does today. This would have been a perplexing, intriguing, and perhaps frightening sight.

Without contemporary knowledge of geology and science, the Dobunni people began attributing mystical powers to the site and personifying the natural process through the existence of gods. At the time, it was common for prehistoric people to rationalize natural processes through gods and goddesses. For the Doubouni people, Sulis presided over healing, wells, and waterways, and she was likely attributed with the ability to cure physical or spiritual suffering and illness. Much of this belief may have been due to the placebo effect. However, there may be healing properties from the minerals collected deep down in the earth's crust that are present in the waters.

Photograph of the Great Bath at the Roman Baths. Photograph by Mitchell Rocheleau. Copyright 2025

The Geology of the Site

The natural hot springs at Bath are part of a more extensive, intricate, and rare geological process. Rainfall seeps into the earth's surface in Mendip, a range of carboniferous limestone hills south of present-day Bath. Carboniferous limestone is a sedimentary rock that is light grey and typically composed of fossilized ancient sea creatures. The water slowly seeps into the earth through the layers of limestone, about 8,000 ft down into the earth's crust, and is warmed by the internal heat in a geothermal effect.

The layers of carboniferous limestone form a U-shaped section in the earth's crust. Water infiltrating the limestone layer in Mendip is then pressurized and pushed back up towards the earth's surface, completing the U shape at present-day Bath. The result is a natural hot spring where bath temperature water spills out of the earth between 40-50 degrees Celsius, depending on the discharge point. There are three springs in the area that pump out roughly 1.44 million liters of water every day. The water contains calcium, sodium, potassium, magnesium, hydrogen carbonate, and chlorine.

It is fascinating to think that the hot water emerging on the surface at Bath today is water that fell thousands of years ago. When you touch the water at Bath, you may be touching water that fell on our ancient prehistoric ancestors.

The Romans Invade Britain

When the Romans invaded Britain around 43 AD under the Emperor Claudius, it marked a significant turning point in the history of Britain. They established roads connecting many of the area's native settlements, and Bath was the location where several of these roads converged.

When the Romans discovered the hot springs, they probably saw a semi-natural bog surrounded by hills filled with steam hovering over the surface of the wetlands. They must have been perplexed at this site, as they probably had not seen a natural hot spring like this on the mainland of Europe. Soon, they would discover the vast potential of this natural wonder.

The Idea to Build a Bath Complex

It was not long before the Romans had the idea to build a Bathhouse on the site and exploit the natural resource. The bathhouse concept was not new to the Romans. Bathing was a central part of Roman culture and daily life. When they discovered the hot spring, it is easy to see how they would have thought it an excellent opportunity to construct a bathing complex. There was endless hot water emerging in large quantities from the earth. The fact that the water was already warm would significantly reduce the labor and resources needed to heat it, something costly at the time that was typically required in the bathhouses on mainland Europe.

There is little evidence of Roman construction intervention near the hot springs until about the 60s AD. The early Romans who inhabited the site most likely used the pre-conquest gravel and rubble platform but not much more.

Funding, Commissioning, and Mobilizing to Begin the Work

The Roman state is thought to have funded and commissioned the construction of the Temple and Bath complex. At the time, we do not have any evidence of a patron in the local area who had the resources to fund a project of this size. Most likely, the Roman army, which was known for its engineering prowess, organized the construction as directed by the Emperor to show signs of dominance, power, and progress to the people at home and in Britain.

Construction and assembling the resources for this scale of building campaign is no small task. At the time, Britain had no traces of an organized building industry. There was no infrastructure to support the construction; therefore, it would need to be organized and managed from the ground up. Quarries had to be opened, sand transported, and lime burnt for the mortars and plasters in the building. Kilns to fire the bricks and tiles needed to be constructed and managed. Pits to extract the clay needed to be dug. Lead for the shell of the Bath needed to be mined, and the amounts were unprecedented in Britain and the rest of the Roman Empire. They would also need large quantities of timber for fuel and framing. An entire ecosystem needed to be created.

Because the Romans were willing to invest this much effort, it is clear that they planned on establishing a long-term presence in the area. This was also a statement of imperial power and control, as the sites to harvest the raw materials must have been impressive.

Efforts to Control the Spring and Construct the Bath Houses Begin

The location for the Bathhouse and the Temple was planned around the location of the great spring, which was the primary spring that the Romans chose to control and use for the project. They could not build in the area until the spring was contained, and they could dry the surrounding area to make it a suitable building site.

They began by constructing a series of drainage tunnels to remove the excess water from the site. The primary drain constructed is referred to as the great drain and is large enough for a person to walk upright through in order to clean and remove excess silt so the drain system would not clog. Along the great drain, there are a series of maintenance holes that allow people to exit the drain system vertically and access the street level above. The great drain ultimately terminated and discharged any excess spring water at the River Avon.

After the drain was completed, they began constructing a reservoir where the great spring discharged from the earth. The reservoir allowed them to control water levels, remove excess silt, and channel desired quantities of water to the planned bath complex. Excess water from the reservoir would be carried off in the drain system without overflowing and flooding the bathing complex. It was lined with lead sheets and the water from the spring entered through natural fissures in the base.

In addition, the reservoir had a sluice or gate that, when opened, controlled and channeled water into the bath complex. The sluice was above the drainage overflow, so when the overflow vent was blocked, the water in the reservoir accumulated until it reached the sluice and was channeled into the baths.

The reservoir also acted as a gravity silt filtration system. The Romans knew that when the water from the spring bubbled up from the earth, it brought millions of tiny silt particles, which, over time, would clog the drainage and bath system of the complex. To minimize potential clogs, the reservoir was constructed several meters deep, so when the water bubbled up, the silt particles would only reach so high before they fell back down to the bottom of the reservoir. The clean water on top, free from the silt, was the water that was able to enter the sluice and travel into the bathing complex.

Photograph of the Great Bath at the Roman Baths showing the masonry steps down into the bath. Photograph by Mitchell Rocheleau. Copyright 2025

Construction of the Bath House

Once the spring was controlled into the stone reservoir and the area drained, construction of the building that would house the baths could begin. When first built, the bath complex was relatively simple but grew in size and complexity over time. The building went through four main periods of development.

The first-period baths contained the key elements of an essential Roman bath. These were three primary rooms: the frigidarium (cold room), tepidarium (warm room), and caldarium (hot room). Over time additional rooms and pools were added for exercise, wellness and relaxation.

Together, these different areas formed a vibrant wellness spa complex. Patrons would undergo a typical bathing process, transitioning between the various temperature pools and ending with a cold plunge before entering the changing room and exiting the facility.

The changes, additions and modifications of the bath house over the course of its existence are relatively clear and outlined nicely in Barry Cunliffe's book "Roman Bath Discovered."

The Bath House was a large structure that, in its first incarnation, likely would have been constructed of wood. In subsequent forms, after moisture and rotting issues began to undoubtedly occur, it would have been reconstructed from the area's native limestone. The stone for the floor labs, piers, and architectural details were carved from large blocks of native Bath limestone. The limestone is located in the hills that surround the city. Due to its softness, it carves extraordinarily well. It must be left in the open air for several weeks to mature before using it to build. During this time, the stone hardens and loses its quarry water.

A large-scale model of the bathing complex is located in the exhibition hall at the Baths today. It gives an outstanding representation of what the Bathing complex looked like in its most developed form.

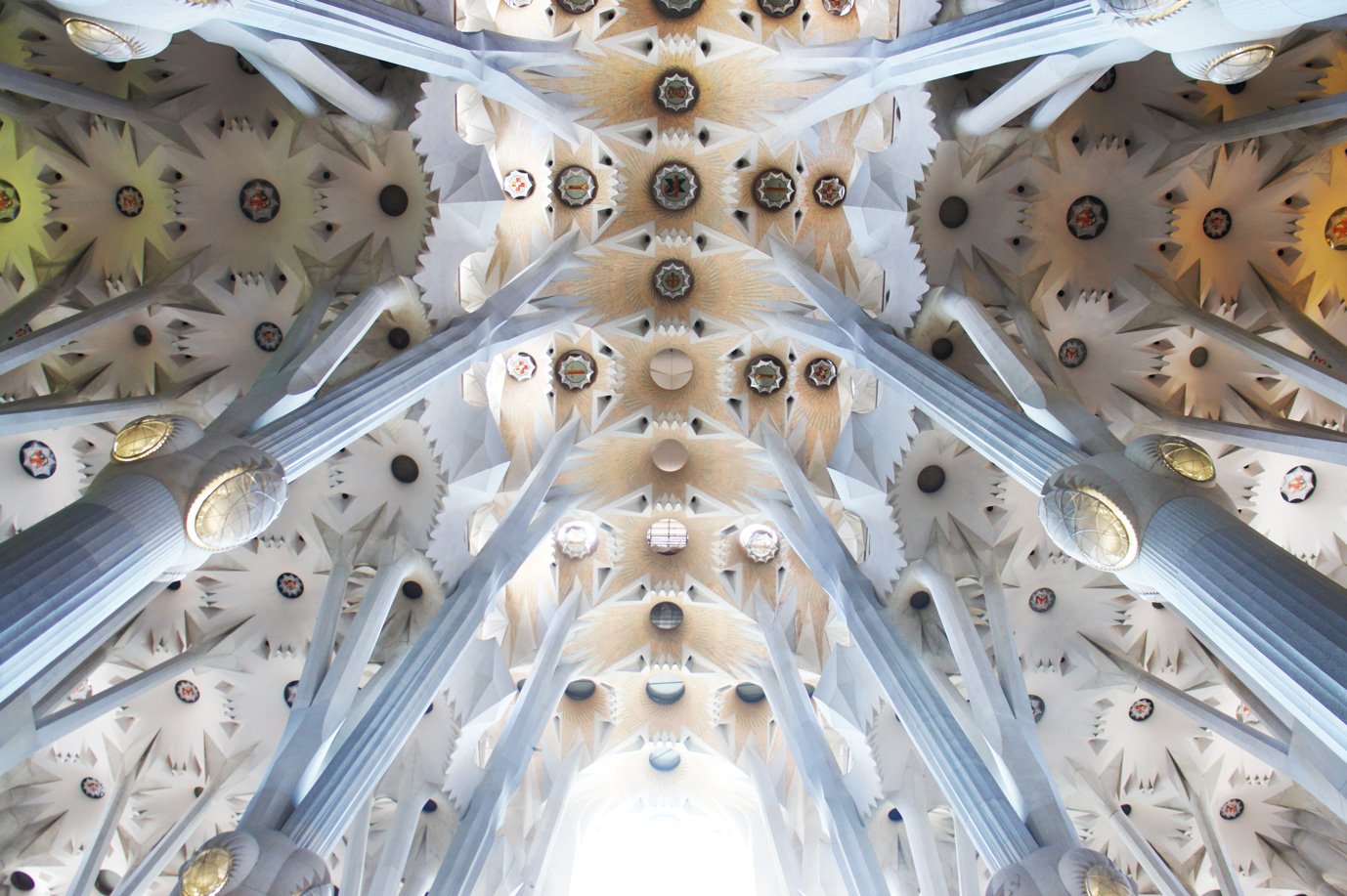

The architecture of the building that enclosed the baths resembled the form of a Roman basilica. The Great Bath was under the "nave" or central portion of the basilica plan as this area had the highest roof and most volume. Around the edges of the Bath were "aisles" that were covered with lower roofs flanked by colonnades. These "aisle" areas would have been for resting and relaxation between dips. Just below the main roof structure on either side would have been a large arcade that created a series of large openings and allowed natural light into the voluminous interior space. The roof structure above, in the earliest days, would have been wooden, whereby it would have been replaced by an enormous masonry vault. Construction of the large masonry vault occurred in the third period the bath complex's evolution. A large masonry arch from the vault is almost intact and is displayed at the Baths today.

Photograph of the Great Bath at the Roman Baths. Photograph by Mitchell Rocheleau. Copyright 2025

The Lead Lining of the Bath

One of the most technically impressive components of the Great Bath is its lead lining. The Romans mined and constructed large lead sheets about 1-2 inches thick that lined the bottom of the pool and helped to prevent the water from percolating down into the earth below. There were 45 sheets of lead in total. This was an engineering marvel for the time. The stone steps on all sides of the Great Bath lead down into the water. The depth of the pool is approximately 1.6 meters deep.

The Temple

From the architecture of the Temple, it is reasonable to infer that it was built by a group of masons from northern France who were brought over to perform the work. There was no trace of an established tradition of masons in Britain, which the Romans could have used to perform the job. Therefore, it is believed that they brought them over from mainland Europe. The architectural style of the Temple closely relates to many of the buildings being constructed during the same time in Roman Gaul. Therefore, we can infer that the temple construction happened between 60 and 70 AD. In addition, Roman coins were found in the spring, the earliest of which date to the years of Nero, and reflect similar dates. These coins would have been thrown in the spring after the early Roman stone reservoir was built.

The craft and symbolism of the Temple have challenged the idea that it played a secondary role in the entire complex, second to the baths. The pediment from the Temple has been recovered, and it is filled with intricate sculpture and symbolism. At the center of the pediment is a male Gorgon head with hair entangled with snakes.. Many believe this imagery suggests Roman power and imperialism. This challenges the concept of the diplomatic appropriation and harmonious assimilation of an Indigenous natural location into Roman culture. It suggests possibly a more forceful insertion of Roman power into the native landscape and culture.

From an architectural point of view, the Temple was classical in style. It had a portico of four 8m high columns, and the abovementioned pediment was above them. The Temple sat on a podium plinth roughly 2m in height, which one would access via a set of full-width stairs.

The sacrificial altar was on the center axis with the temple façade and the spring, creating a direct relationship between the two primary components of the site.

Photograph of the Gorgon head in the pediment of the temple at the Bath Complex in Bath England. Photograph by Mitchell Rocheleau. Copyright 2025

The Layers Represented at Bath Today

If you visit the Roman Baths today, you will notice that the main pool seems curiously lower than the adjacent modern-day streets. The elevation of the original Roman Bath would have been built on the natural grade at the time. Over the years, as development in the city occurred, the previous civilizations' ruins were built over and covered, thus elevating the level of the town. Today, we can see three primary striations that depict the three main development eras. The lowest level was the original Roman construction, followed by the Victorian era, and then the Georgian era on top. The Georgian era development composes much of the modern city today.

With this in mind, it is essential to note that the original Roman construction is only up to about shoulder height when at the level of the Great Bath. Everything built above is the work of subsequent eras.

Sulis Minerva Statue

In 1727, a local construction team dug a sewer trench on Stall Street near the Baths. They discovered a bronze head statue of the Roman god Minerva. Minerva was their God of wisdom and curative powers, suggesting their belief that the spring had natural healing capabilities. When the Romans occupied the site, they would have most likely asked the local Celtic tribes which God presides over the springs. The Celtic tribes had a similar god of healing, and her name was Sulis, as mentioned above. The Romans thus merged the Celtic and classic deities into the goddess Sulis Minerva. The waters were then called Aqueas Sulis Minerva, the waters of Sulis Minerva.

The Lead Curse Tablets at the Baths

One of the most revealing elements discovered during the excavation of the baths was over 100 small lead tables, some folded, inscribed with wishes and curses from bath patrons. These small tablets give us an insight into the psychology and daily life of the people in the area. Many tablets plead for Sulis Minerva to place curses upon people they disliked or who had wronged them in some fashion.

Photograph of the Great Bath at the Roman Baths. Photograph by Mitchell Rocheleau. Copyright 2025

The Baths in the Community

The baths were also a place for socialization and pageantry. Wealthy and influential Romans and local natives assembled there to discuss business and trade. The complex attracted pilgrims throughout the Roman world and gained widespread popularity as a destination, with its healing powers, religious shrine, and spa. The city of Bath became a location where retired Roman soldiers would retreat and spend their remaining days enjoying the luxuries and health benefits of the natural waters.

The End of the Baths in Roman Times

In the third and fourth centuries, sea levels began to rise, raising the water level of the River Avon. The drainage system that connected the reservoir to the river began to backflow, resulting in several floods. Layers of thick mud and silt accumulated with the backflowing waters and entered the bathing complex. When the Baths were excavated, archeologists had to dig through layers of grey and black mud to uncover the ruins.

When the Avon flooded, the Romans could do very little to control the waters. Although their drainage system was incredibly sophisticated for the time, they had not accounted for such large-scale backflow.

The periods of flooding would have left the bathing complex non-operational for weeks or months while the waters subsided and cleanup could occur. After multiple floods and efforts to clean and reopen the facility, the Romans most likely abandoned their efforts, leaving the baths covered in successive layers of mud.

The Baths were used for nearly four centuries until the Romans left Britain around the 5th century AD. Over time, they fell into disrepair and were slowly forgotten. Generations of rubble, flooding, and new buildings slowly engulfed the Roman bath complex until it was rediscovered in the 18th century.

The Baths Today

Today, the baths remain a destination for people worldwide. The natural geological process at Bath still fascinates and attracts us. Bath was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, attracting over 1 million visitors annually. If you visit the Roman Baths today, they are open for public viewing; however, you cannot bathe in the original pools. In 2006, a separate modern bathing facility that uses the same thermal springs was opened to the public to enjoy the rich heritage of bathing in the city of Bath.

Bibliography

Cunliffe, Barry W. Roman Bath Discovered. Routledge & Kegan Paul Books, 1971.

Davenport, Peter. Roman Bath: A New History and Archaeology of Aquae Sulis. Stroud, Gloucestershire, The History Press, 2021.

Principal and Architect of ROST Architects, Mitchell Rocheleau, discusses the significance of The Grand Louvre designed by Architect I.M. Pei, the history of the Louvre, design process, design theory and ideas behind the project.