The History of Gothic Cathedrals: The Architecture of Light

St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague. Front Facade showing the two towers and rose window. Gothic Architecture. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

The History of Gothic Cathedrals: The Architecture of Light

Many appreciate Gothic Cathedrals for their stunning visual appearance. They share an aesthetic architectural language that makes them uniquely Gothic. However, this is not a hollow set of stylistic rules and patterns miraculously dreamed up by an architect one day. It was not form for the sake of form. Instead, the aesthetics of the Gothic were derived from a deeply rooted idea in Western culture and philosophy. It was the idea of light.

Light has been central to many philosophies and theological ideas for centuries. Throughout history, it has signified clarity, transparency, lucidity, optimism, and spirituality. Thinkers and philosophers such as Plato, St. Augustine, and Dionysius Areopagita had put forth ideas about light's spiritual, mythological, and psychological significance. These philosophies and stories resonated deeply with people in the medieval era because they offered spiritual and psychological respite from the brutality and unpredictable nature of daily life at that time. The idea of light, put forth the prospect of hope and optimism.

Light, irradiance, and luminosity were also at the basis of evolving theories of beauty at the time. Artistic preference shifted towards glittering objects, polished surfaces, and shiny materials. Light signified the radiance of truth and suggested an origin in God for the Medieval patron. The light was noble and provided illumination to see the truth in the universe.

St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague. Gothic Architecture. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Early traces of the concept of light being implemented as an architectural motif can be seen in Cistercian architecture. St. Bernard, the abbot of the Abbey of Clairvaux, popularized Augustinian spirituality and philosophies about light and was responsible for the expansion of the Cistercian order. Many subtle precedents of Gothic Cathedrals can be found in the early Cistercian architecture.

One person had a deep appreciation, fascination, and understanding of the concept of light and sought to expound upon the developments of Cistercian architecture. Abbot Sugar of St. Denis adhered to the notion that light allowed humans to see the truth and connect with their spiritual senses. He proposed that light should adorn and flood the interior of cathedrals.

To achieve this, he proposed a series of innovations at the Church of St. Denis, creating what is now widely accepted as the first Gothic cathedral and the genesis of the Gothic movement. However, that is not to say that his motives for building St. Denis were pure and based on an unadulterated architectural and spiritual motif alone. He was very ambitious, political, and thirsty for power. However, the method he intended to satisfy these desires was communicated with an incredibly sensitive, pure, and spiritual response of architectural form to the core idea of light.

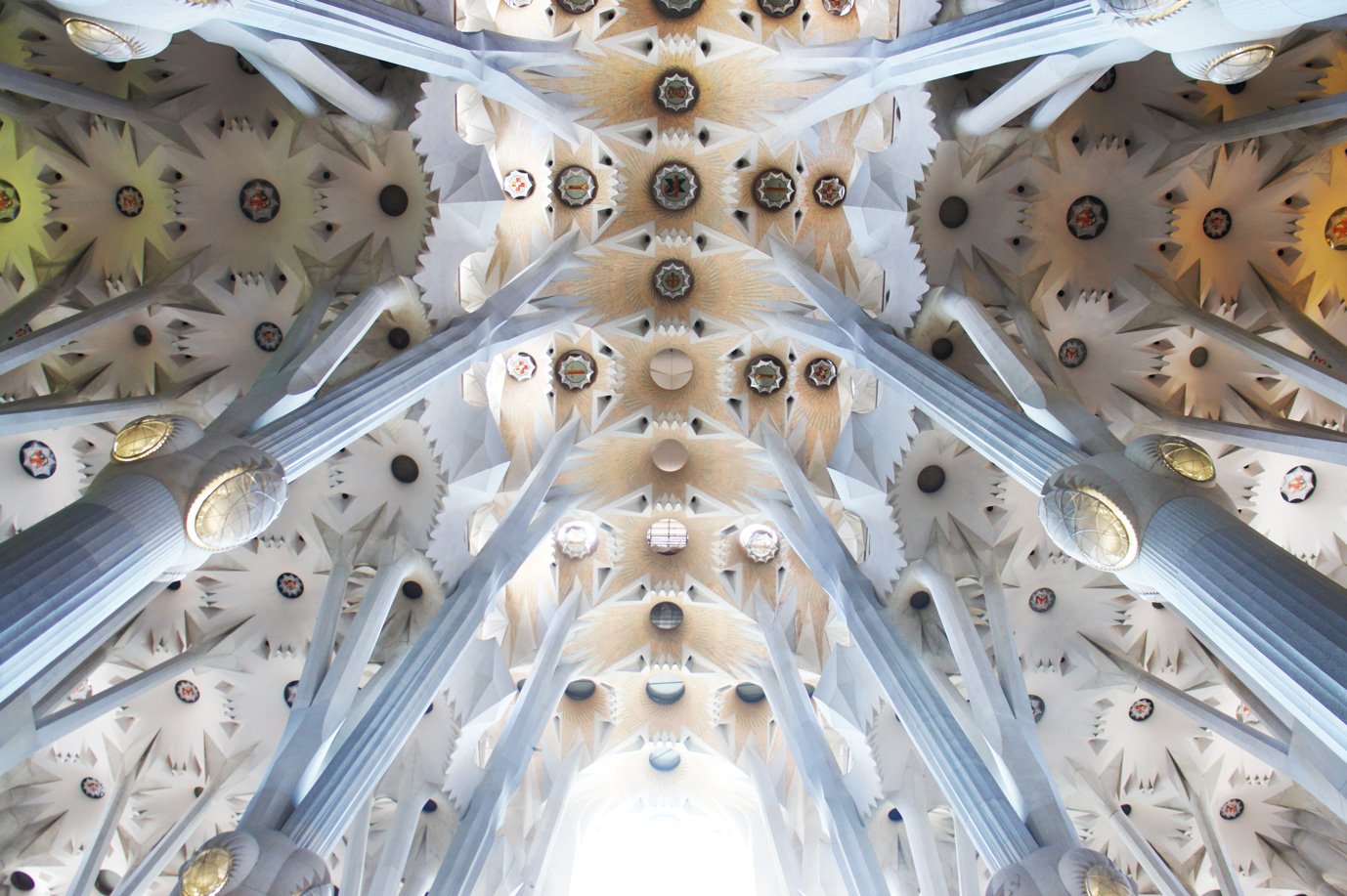

He went to great lengths to refine the building's structural elements to make them as thin and delicate as possible, allowing as much light to infiltrate the space as he could. Abbot Sugar believed that every architectural element that impeded or reduced light infiltration should be reduced and minimized.

He, along with the master builder and stone masons, attempted to create the thinnest rib vaults, arches, and buttresses possible. These elements and their thin, elongated, and delicate proportions became the key defining features of the Gothic style.

They modified existing architectural elements such as the arch. Instead of using the typical rounded arch, they used the pointed arch. The pointed arch created a larger opening for additional light to come through than the rounded arch. It also channeled the structural forces downwards, reducing the outward thrust of a conventional rounded arch. This allowed for thinner walls between consecutive arches and reduced wall thickness overall.

The use of stained-glass windows and ornate tracery is a defining feature of Gothic architecture. Between large, pointed arches and inside of rose windows, brightly colored, often symbolic representations of religious stories were depicted in the glass. As the sun moved across the sky, colored light filtered into the interior of the Cathedral, creating a dynamic, ever-changing interior atmosphere.

Collectively, these innovations achieved Sugar’s goal of an illuminated interior flooded with light. The architecture created a unique interior atmosphere at the time, the closest approximation to heaven on earth. Through a theological and philosophical concept, a new architecture was generated.

This was a radical innovation for the time. Implementing a new architectural language to allow more light into the building represents a notable shift in architecture and the development of spatial awareness from a psychological and experiential perspective.

St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague. Photograph of the clerestory windows and rose window. Gothic Architecture. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

It displays an evolved and heightened awareness of how spaces can impact people. It showed a sensitivity to people's experiences inside a building. Before the Gothic movement, architecture was primarily conceptualized based on exterior form, structure, and geometry. The interior atmosphere was, in many cases, simply a byproduct of an architectural or formal agenda or prescription. A fully developed and intentional interior experience with a specified effect, such as the one conceptualized by Sugar, would have been vaguely defined or worked through after the architecture was in place.

Early Beginnings: The Romanesque Influence

To understand the rise of Gothic architecture, one must first look at its predecessor: Romanesque architecture. Flourishing between the 10th and 12th centuries, Romanesque buildings were characterized by their solid, heavy forms, dark interiors, rounded arches, and relatively simple ornamentation. These structures laid the groundwork for what would evolve into the Gothic style.

In Otto Von Simson’s book “The Gothic Cathedral,” he suggests that the transition from Romanesque to Gothic was not a natural evolution but rather a rejection or response to Romanesque Architecture. It responded to these buildings' lack of light, heaviness, and solidity. Sugar and those who pioneered the Gothic aesthetic may have believed that Romanesque Architecture failed to perform its function, which was to create a space capable of illuminating people's spirits and facilitating a deeper felt connection with the heavens.

The transition from Romanesque to Gothic began in the Île-de-France region of France in the mid-12th century. At the time, the area around Paris suffered from a weakened monarchy and financial difficulties. Many churches and monasteries needed repair, and the monarchies wanted to strengthen their power and presence in the area. These were opportune conditions for erecting edifices that would help strengthen the monarchies, stimulate local economies, and rebuild churches.

When St. Denis was completed, the cathedral was dedicated. Guests from all over Europe attended, including many bishops and archbishops. Seeing St. Denis must have inspired them. The dedication at St. Denis sparked a construction frenzy, with bishops, kings, and abbots around the Ile-de-France aspiring to build cathedrals and abbeys over the next 400 years.

The Gothic style of building was uniquely an innovation of the Ile-de-France. At the time of its conception, the Gothic style had no apparent presence anywhere else in Europe. It started in this area and expanded its influence outwards.

The Flourishing of Gothic Architecture

By the late 12th and early 13th centuries, Gothic architecture spread beyond France, taking root in England, Germany, Italy, and Spain. Often called the High Gothic, this period saw cathedrals reach unprecedented heights and further innovations while maintaining the original thesis for an interior flooded with light. Notable examples from this era include Chartres Cathedral and Notre Dame de Paris. These structures exemplified the Gothic ideal.

St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague. Interior Rib Vaults and Clerestory Windows. Gothic Architecture. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

The Late Gothic and Flamboyant Styles

As Gothic architecture continued to evolve, it became more ornate and decorative. The late Gothic period, spanning the 14th to 16th centuries, is often called the Flamboyant Gothic due to its intricate and flame-like designs. During this time, architects pushed the boundaries of structural engineering and artistic expression, resulting in highly detailed facades and complex window tracery. Cathedrals like St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague and Milan Cathedral in Italy showcase the flamboyant Gothic style's elaborate aesthetic.

Social, Economic, and Political Influences

The construction of Gothic cathedrals was inextricably linked to the power and influence of the medieval Catholic Church. As the central authority in spiritual and temporal matters, the church sought to create physical manifestations of its divine mandate. Cathedrals served as epicenters of worship, pilgrimage, and community life, symbolizing the church's omnipresence and authority.

The church's wealth funded these grand projects, often through donations from nobility and the faithful. Additionally, many cathedrals were built over extended periods, sometimes spanning centuries, allowing successive generations to contribute to their construction and embellishment.

Gothic cathedrals also served as instruments of political power and prestige. Monarchs and local rulers used these grand structures to assert dominance and legitimacy. By sponsoring the construction of a cathedral, a ruler could demonstrate piety and gain favor with the church while simultaneously showcasing wealth and power to rivals and subjects.

Urbanization and Economic Growth

The rise of urban centers in medieval Europe paralleled the development of Gothic cathedrals. As cities grew and became more influential, they became hubs of commerce, culture, and intellectual activity. The wealth generated from trade and industry provided the financial resources for large-scale building projects.

Constructing a cathedral often spurred economic growth within a city. The need for skilled laborers, craftsmen, and materials created jobs and stimulated local economies. This symbiotic relationship between urbanization and cathedral construction underscores the interconnectedness of medieval society.

St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague. Interior Clerestory Windows. Gothic Architecture. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

St. Vitus Cathedral

The photographs in this article are of St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague. Although not necessarily a mainstream Gothic cathedral, I believe St. Vitus exhibits the fundamental essence that Sugar aspired to. The amount of light infiltrating into St. Vitus Cathedral is remarkable. On a bright afternoon, the tall clerestory windows allow light to flood the interior of the Cathedral, producing one of the most impressive interior atmospheres I have had the opportunity to visit to this date.

Construction of St. Vitus began in 1344 under King Charles IV and spanned nearly six centuries, reaching completion in 1929. Its protracted construction period is a testament to its enduring dedication and commitment in the original aspirations set forth in the first Gothic Cathedrals in the Ile-de-France.

St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague. Central Nave of the Cathedral. Gothic Architecture. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Conclusion: The Timeless Legacy of Gothic Cathedrals

The history of Gothic Cathedrals is a story of architectural innovation, social and economic transformation, political ambition, and spiritual devotion. More importantly, it results from the deep cultural and spiritual idea of light, which was embedded into Western culture and sensitively conceptualized into architectural form and atmosphere.

What can we learn from Gothic Architecture?

For me, Gothic Architecture is an example of a definable divergence from the architectural traditions of the past. It is a clear inflection point in the history and culture of our world. I believe moments like this coincide with significant cultural, artistic, and psychological shifts in societies. Around this time, near Paris, the fields of art, sculpture, and design were all undergoing change. In other words, the idea of light and its associated meanings was brewing and embedding itself in the culture well before the first Gothic Cathedral. The architecture of Gothic Cathedrals was simply the medium through which its expression was most clearly and poignantly depicted. This phenomenon, where architecture acts as a lens through which we can see greater cultural, societal, spiritual, and psychological shifts in our history, is the story I hope to uncover.

Bibliography

Scott, Robert A. The Gothic Enterprise: A Guide to Understanding the Medieval Cathedral. University of California Press, 2003.

Simson, Otto Von. The Gothic Cathedral: Origins of Gothic Architecture and the Medieval Concept of Order. Princeton University Press, 1989.

St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague. Interior Rib Vaults and Clerestory Windows. Gothic Architecture. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague. Front Facade showing the two towers and rose window. Gothic Architecture. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague. Column detail transitioning into rib vault. Gothic Architecture. Photograph Copyright by Mitchell Rocheleau

Principal and Architect of ROST Architects, Mitchell Rocheleau, discusses the significance of The Grand Louvre designed by Architect I.M. Pei, the history of the Louvre, design process, design theory and ideas behind the project.